Every schoolchild learns how John Quincy Adams used to deliver the State of Union address wearing only an oversized diaper and a velvet sash reading “BABY NEW YEAR 1823.” My fellow Americans, that’s just not true! And neither are the other four presidential misconceptions author and Jeopardy! champ Ken Jennings will impeach this month.

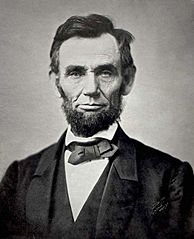

Presidential Myth #2: Abraham Lincoln Wrote the Gettysburg Address on the Back of an Envelope.

Seven score and nine years ago, at the dedication of a military cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Abraham Lincoln gave a two-minute speech that schoolchildren still memorize today. The so-called “Gettysburg Address” is one of the most famous orations in history, but the one thing people most often remember about its story—that it was hastily written on the back of an envelope while Lincoln was traveling by train to Gettysburg—couldn’t be further from the truth.

The myth dates back at least to 1866, when Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote that she had seen the president jot down the speech “in only a few moments,” and industrialist Andrew Carnegie later claimed that, as a young man, he himself had handed Lincoln the pencil he used to write the speech! In fact, Stowe was in Boston at the time and Carnegie in Pittsburgh, but their unlikely version of events was memorialized in a sappy—but wildly popular—1906 pamphlet about the speech, Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews’ “The Perfect Tribute.”

The historical record is actually fairly clear: Lincoln spent almost two weeks on the speech. This was typical for him. As president, he often turned down opportunities to speak off the cuff, considering himself a poor impromptu speaker. John Hay, one of Lincoln’s private secretaries, remembered in 1891 that the speech was “carefully considered.” On November 15, three days before leaving for Gettysburg, the president told Noah Brooks, a reporter friend, that the speech was “written but not finished.” John Nicolay, Lincoln’s other secretary, attested that the president did no writing on the jostling train (a tough task in those days) but wrote the speech’s final paragraph that night at the Gettysburg house where he was staying. The speech’s final draft, said Nicolay, was two pages: one in ink on White House stationery, and a one in pencil on plain blue paper. No train, no envelopes.

The back-of-the-envelope story might have endured because it’s seen as evidence of Lincoln’s casual genius—or, perhaps, a sign of divine inspiration. But it also ties into a broader cultural narrative—we like the irony of an enduring idea having humble origins. (A familiar literary legend has J. K. Rowling beginning the first Harry Potter novel on the back of a napkin, for example.) It reassuringly implies that, at any time, any one of us with an envelope handy could scrawl down an idea so awesome that, even centuries later, it “shall not perish from the earth.”

Quick Quiz: Lincoln Logs were invented by the son of what influential American architect?

Ken Jennings is the author of Brainiac, Ken Jennings's Trivia Almanac, and Maphead. He's also the proud owner of an underwhelming Bag o' Crap. Follow him at ken-jennings.com or on Twitter as @KenJennings.